As soon as I get back to Pakistan, one of the first things that strikes me is always how normal it all feels. It’s been almost a year and a half since I last saw my parents, but the instant I’m here, it feels as though I never left. From the moment I saw my parents’ faces waiting outside the “Arrivals” door at Jinnah International Airport in Karachi, everything has felt so familiar. At home in Hyderabad I flop onto my parents’ bed with a book, enjoying the fan, while I interrupt my dad at his desk now and then with a question, or whatever I happen to be contemplating at the time. Or I float in and out of the kitchen, talking to my mum, getting fruit from the fridge and making trips to the cooler to fill my yellow plastic KFC mug that each of us kids have had since early elementary. Everything is so familiar that I can hardly convince myself this is different, that it’s just a week of my year — a week I get to spend at home in the Sindh.

There’s something so strangely normal about finally getting where you’re going — finally sitting right there with the person you’ve waited months to spend time with, or sitting there in the car with your parents as you drive back from the airport, a year and a half later. I almost forget it wasn’t like this yesterday. And somehow I want being here to feel as foreign and special as it seemed during the months waiting to be here, but now that I’m here, it’s just not the way it is. It’s all too familiar.

But as I’ve spent these days enjoying the short time I have here in Pakistan, I’m realizing maybe unfamiliarity is overrated. The sense of exoticism, adventure and exploring new places is wonderful, but there’s something very ordinarily magical about the feeling of normal — of familiarity. To be around the people who you don’t have to be anyone with. To know and be known. To be somewhere where you just belong. That’s what home feels like.

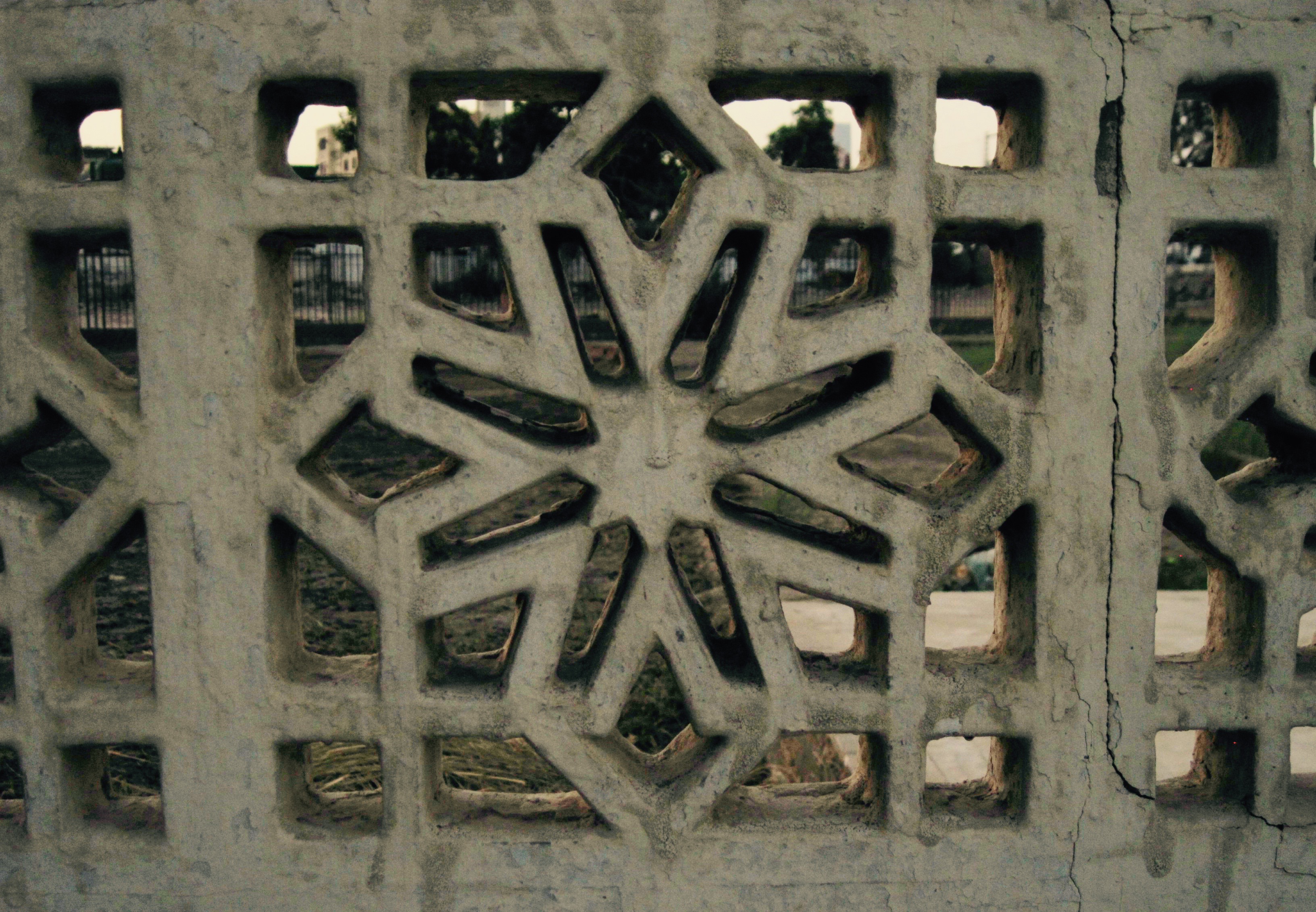

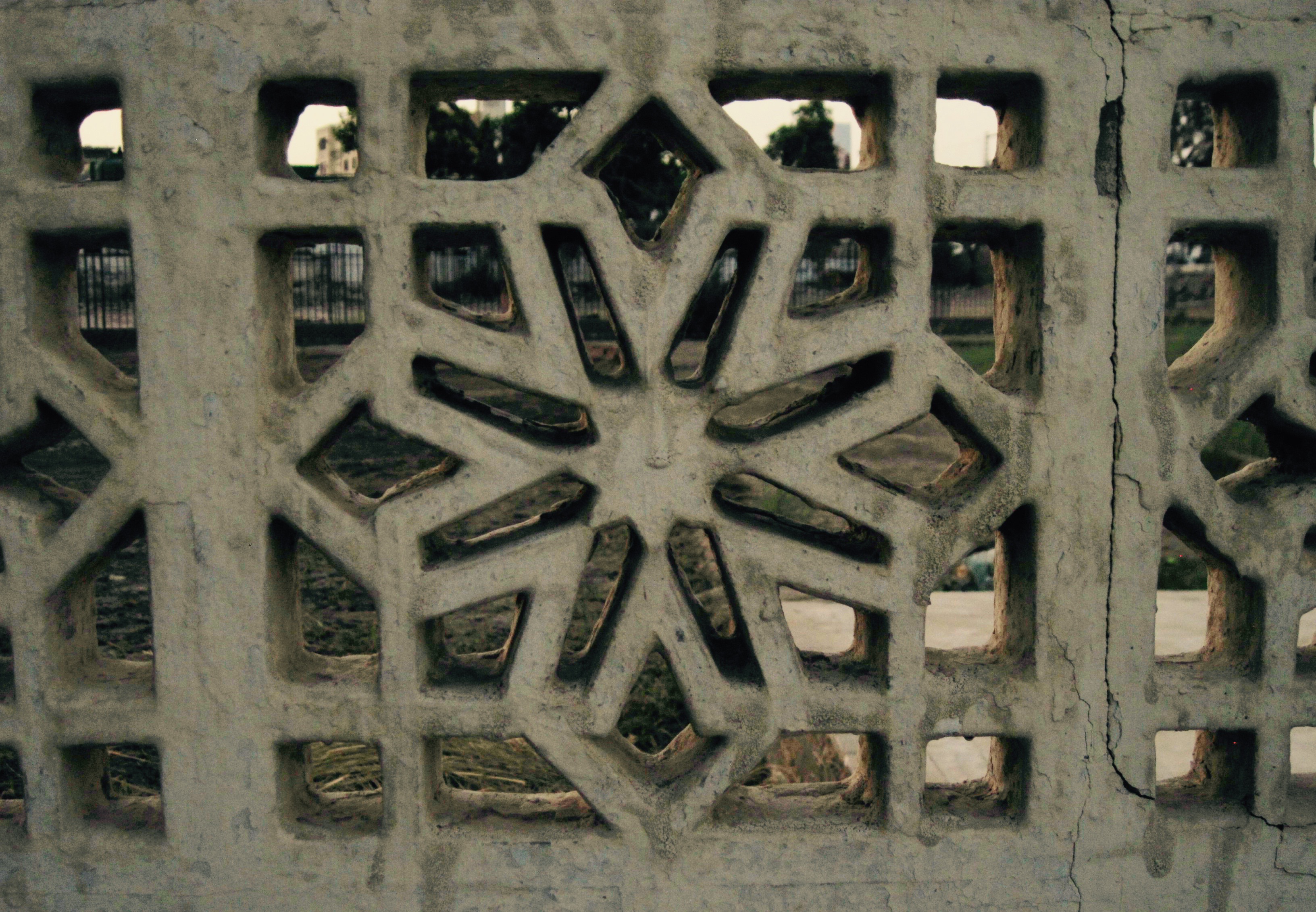

I had to tell myself it’s okay to feel normal. While in the Sindh, I felt like I should be taking pictures or writing, to capture and communicate the beauty of the Sindh that I so enjoy, but I just couldn’t find the motivation. I wanted to share it with those who haven’t seen it or been here, but inwardly I resisted, because deep down, I didn’t want to document it. I wanted to just be. I wanted to be myself, at home — to enjoy going to visit with old friends, navigating through the crazy city traffic downtown with my dad, and lying under the dark sky of glow-in-the-dark stars that covers the roof of my room. I didn’t realize how much I just need to be sometimes — to just be thankful a place, people or a moment in silence. To let it wash over me and bask in the feeling of being home, finally.

I’m learning to enjoy the familiar. Of course, there will always be change and feelings of newness, even in a place that’s normal. Nothing stays the same forever. Even visiting a old place comes hand in hand with some of the pains of seeing it changed and different than I left it. But I’ve realized the value of feeling normal. I’ve realized that there’s a reason the word familiar begins with “family” (almost). Because there’s something so wonderfully refreshing about being back with family, and to embrace that familiar feeling of being around the ones you love, after months and months of being apart — to belong somewhere and to belong to someone.